Of all the agents which cause diseases in plants, animals and humans, viruses are the most intriguing, the most baffling and, unfortunately, the most difficult to combat. Like the winds of a hurricane, you cannot see them but you can see the effects which they produce.

Modern understanding of the nature of viruses dates back less than 125 years even though virus diseases of plants and people were described or known to exist hundreds and even thousands of years earlier.

The word “virus” is from the Latin meaning “poison.” This name was first given to these substances in 1898 by Martinus Beijerinck, a Dutch microbiologist, who first demonstrated that they consisted of a “contagious living fluid.” A few years earlier Dmitri Iwanowski told the Academy of Science in St. Petersburg how he passed the juice from virus infected tobacco leaves through a porcelain filter with pores so fine they screened out bacteria, and how he successfully reproduced the disease (mosaic) in healthy plants with the filtered, bacteria-free juice. This is recognized as the first demonstration of a filterable, infectious agent in either plant, animal, or human pathology.

Viruses cause diseases in humans such as influenza, poliomyelitis, smallpox and measles, and in animals they cause rabies, parrot fever, and hoof and mouth disease. Even bacteria contract virus diseases.

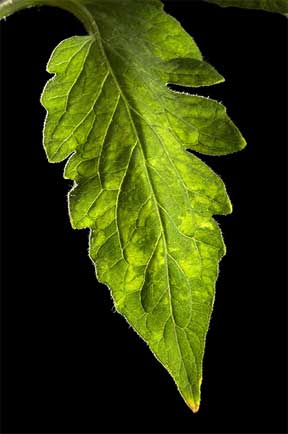

In plants, these mysterious substances impair or destroy chlorophyll, the highly essential substance which helps to build food for plants. If the impairment or destruction is general, the leaves turn yellow or chlorotic. If it occurs in patches, spots, or streaks, the leaves assume a mosaic mottling, a spotting or a streaking. The overall effect in most instances is one of slow degeneration and eventual death of the plant.

Plants actually increase in value when infected by a virus in rare instances. The so-called flowering maple, Abutilon striarum var. Thompsoni, has yellow and green blotched leaves that enhance its appearance. A class of tulips is a virus-infected strain in which streaks of different hues appear in the flower petals in place of the normal single color of the variety. In the time of the French kings, a single mosaic infected tulip bulb sold for as much as one thousand dollars. Today we know that when such tulips are planted near healthy varieties, the entire planting will soon become infected.

The number of plant viruses is unknown, but nearly hundreds have been recognized and described with some degree of accuracy. Some, like aster yellows, can infect a wide range of plants including vegetables such as carrots, tomatoes, lettuce and onions; weeds like plantain, chickweed, dandelion; and ornamentals including China aster, chrysanthemum, marigold, petunia and snapdragon. Some plants can be infected by more than one virus at the same time, thus complicating both the symptoms and effects.

Tobacco Mosaic

Tobacco mosaic has been the most extensively studied virus because of the ease with which it can be transmitted from plant to plant merely by rubbing healthy plants with the infectious juice. Not only was it used by the virus pioneers late in the late 1800’s, but in the early 1930’s it was the first virus to be isolated in pure form and shown to be a crystalline protein by Doctor W. M. Stanley, at the University of California.

As a matter of fact, what many consider one of the greatest contributions ever made in the virus field came from Dr. Stanley’s virus laboratory. Doctors Fraenkel-Conrat and Robley Williams assembled a virus in a test tube from inactive materials! This was accomplished by first separating the tobacco mosaic virus into its two principal components, protein and nucleic acid, neither of which can infect plants. They then put the two parts together again and were able to produce infections with reassembled material!

The implications of this work are to the field of biology what harnessing of the atom was to the physical sciences. Man could now “tailor” viruses by taking them apart and recombining them so they vary from the original. These recombinations can provide immunity to people and plants, without causing disease! They may also help to develop virus antigens, materials which stimulate production of antibodies.

To explain the origin of viruses would be like explaining life itself. Like all forms of life, plant viruses do not arise out of nowhere but come from preexisting forms. We know that new strain variants arise from old stocks just as new varieties of plants arise by the process known as mutation or sporting.

Viruses are composed largely of two substances: nucleic acid and protein.

They are ultra-microscopic in size (measuring in the millionths of an inch), and hence cannot be seen even with the aid of the most powerful microscope. They can, however, be photographed with the electron microscope which uses electron rays instead of light rays. The photographs show them to vary in size and shape. Some are long straight rods, others are short ones, and still others are spherical.

The most unusual property of all viruses, however, is their ability to reproduce themselves, a characteristic peculiar to all living things. Here, then, are crystalline materials (and crystals are considered lifeless) that are capable of reproducing themselves when placed in the proper environment!

Viruses are spread in many ways: mechanically by rubbing or contact; using contaminated knives and pruning shears; by graftage; by means of virus infected seeds, bulbs, tubers, roots, or cuttings; and, most frequently of all, by insects.

Under natural conditions only a few viruses are spread by human contact. Tobacco mosaic is readily transferred during planting and cultural operations after one’s hands have touched a diseased plant. This is one reason we never allowed smokers to come into our orchid greenhouse with a cigarette. They first had to was their hands.

Virus Forever

Once a plant contracts a virus it never gets rid of the virus completely. Hence the use of virus-infected vegetative parts such as cuttings, roots, bulbs, corms, and buds assures continuation of the virus disease. Some seeds also harbor viruses and hence carry the disease from one generation to the next generation. This is a reason tissue culture or cloning in sop important in the plant propagation side of the business.

Sucking insects such as aphids, leafhoppers, white flies and mealy bugs spread virus diseases in much the same manner as mosquitoes spread malaria and yellow fever. The insect inserts its mouthparts into the infected host plant and draws out the plant juices which contain virus. With some viruses, a certain period of time must elapse before the juice taken in by the insect becomes infectious. Some of this infectious juice is later passed to other plants.

If I were asked to single out “Public Enemy Number One” among all insects, I would certainly pick the green peach aphid which feeds on a great variety of fruit, vegetable, and ornamental plants. This aphid is capable of transmitting more than fifty kinds of plant viruses!

Not so long ago scientists thought that plant viruses could only multiply in plant cells. We now know that some of them can also multiply inside animals! The so-called clover club leaf virus, for example, can be passed from one leafhopper generation to the next via the eggs. Dr. L. M. Black formerly Plant Pathologist at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden found decades ago that this virus was still infectious after it was transmitted through twenty-one successive generations of this insect over a five-year period. Dr. Black estimated that the virus in the original female had been diluted 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times. It could not have been infectious after this period, unless the virus actually multiplied inside the insect. Here then is a clear-cut case in which a plant virus multiplied inside an animal (insects as you know, belong to the animal kingdom.

Additional and direct evidence was subsequently provided by Dr. Karl Maramorosch of the Rockefeller Institute succeeded in passing aster yellows virus by needle inoculations through ten generations of virus-free leafhoppers that were never allowed to feed on virus-infected plants.

Soil-borne viruses are known. Although most of them live in soil for only a short time, a few persist in the roots of both living and dead plants from one season to the next, even in cold climates. The big-vein virus of lettuce and the rosette virus of wheat, for example, can contaminate soil in which diseased plants are growing. Healthy plants subsequently grown in such soil will contract the diseases.

The symptoms produced by some plant viruses are so clear-cut that they can be diagnosed readily by any plant pathologist and by many amateur gardeners. But, as with virus diseases of humans, positive diagnosis cannot be made on the basis of symptoms alone. One must inject the juice from the suspected plant, or graft a bud, a piece of root, or bark onto a healthy plant of the same kind, and reproduce the plant disease before one can be absolutely sure of the diagnosis. Obviously such a procedure is used primarily by experimental workers.

Plant viruses are combated by both direct and indirect methods.

Because insects are the principal disseminators of plant viruses in nature, then, theoretically, controlling them should also control the virus. Various chemicals in the past like DDT, lindane and malathion proved to be excellent insecticides for virus spreading insects. But at times even these highly efficient materials do not give complete control. The few uncontrolled insects are enough to spread the virus over a large area.

Another way to combat some viruses is to use care in handling and growing plants. Tobacco mosaic virus is so easily passed to tomatoes that tobacco users should wash their hands thoroughly in soapy water before working in the garden. I have seen nearly every tomato plant in a home garden infected with mosaic where this precaution was not followed faithfully.

Sanitary practices such as weed control also help to keep viruses in check. Many weeds act as virus reservoirs and can carry the virus from season to season. Chickweed frequently is an excellent reservoir for the spotted wilt virus which affects many vegetable and ornamental plants.

Destruction of infected host plants also help to keep viruses at bay. Old tulip plantings are frequently infected with the mosaic virus. In such situations the gardener should be ruthless and should lift and discard every plant, bulb and all, and then replant with new bulbs purchased from a reliable dealer.

Heat, applied directly to infected plants, or to the growing medium, is occasionally employed in the control of viruses.

Perhaps the most practical way of combating some virus diseases is to use virus-free plants from the very start.